Holger Nawrocki Wind power

Worldwide unique system for wind turbine maintenance

How are wind turbines currently maintained?

The plants are currently maintained with two different systems: either using rope-supported industrial climbers or with drones. With the former, you have to stop the turbines, then put the rotor blade you want to document in a vertical position and then abseil down the front and rear and document the damage with a photo camera. When servicing with a drone, the turbine must also be stopped, but the rotor blades can remain in their position. The drone flies around the blade and takes pictures. What distinguishes both methods - or not - is that the plant must be stopped.

Why is that a problem?

Because these downtimes cost the operator a lot of money. The wind turbines must be stopped for half a day to a day. During this time they do not produce any power and cannot feed into the grid. Moreover, wear and tear increases when the plant should actually be running and then has to be stopped and moved into the correct position. Added to this is the deployment of personnel for remote maintenance and the service technician on site.

All conventional maintenance systems definitely increase the cost of documentation. With our system, however, the operator continues to earn money. Because whilst we are carrying out the maintenance, the plant continues to run as normal and feeds power into the grid.

Which system for maintenance and documentation have you developed?

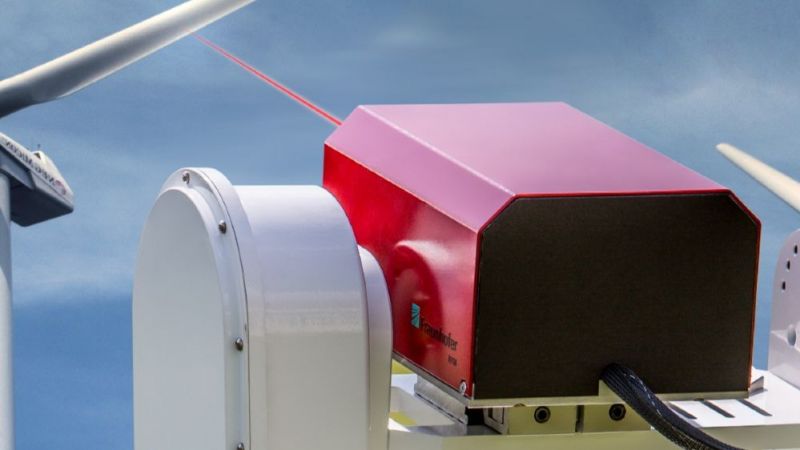

We have developed a photo documentation system for the rotor blades of wind turbines, which works while the turbines are in operation. The documentation camera is installed in a pivot boom. It can move around its own axis. The camera tracks the movement of the rotor ring so that it constantly monitors the selected blade segments. Then we take five pictures of the front and rear of each rotor blade. This gives us high-resolution images of the blade surface.

What exactly is your approach?

We load our photo documentation system into the car and drive to the wind turbines. On site we unload the device and place it in the right position. This is very straightforward, because it can be used quickly and travels on tracks, so we can use it on almost any terrain. Then we align the camera to the rotor blade and start the documentation. The wind turbine simply continues to run. We need about one to two hours per plant to document it completely.

The customer then receives an evaluation report with a high-resolution photo proof and the exact specification of the distance and radius from the hub at which the damage to the blade can be seen. Additionally, we have programmed the software so the system also automatically displays comparative photos and evaluation of the last maintenance. So if you documented the damage to the plant six months or a year ago and now want to check how it has developed, our software will also output the reference with the direct comparison.

What costs can be saved in this way?

We can document four plants a day, 20 plants a week, 80 plants a month and, extrapolating to the year, about 1,000 plants. If a customer has 1,000 plants documented per year, he saves approximately 300,000-500,000 euros per year, depending on the size and utilisation of the plant. As wind turbines become more and more powerful, this is likely to increase in the future. After all, the operator earns no money in the three to four hours in which he normally has to shut down the plant. Added to this are the costs for wear and tear and personnel. We have not even included them in the calculation. We have only considered the pure infeed into the power grid. If you convert this to the price of our photo documentation, you could also say: What the customer pays for our documentation, he saves by not having to stop the plants for several hours. So in principle he gets our service for free.

How long has the system been on the market?

We received the first two units at the end of 2019 and then reworked the software and camera control. The two photo documentation systems enable us to document around 2,000 to 2,500 plants per year. But we are able to act quickly. If a customer tells us that they have a higher demand, we can increase this to a number X within a few weeks.

Are you already in talks with potential customers?

We are currently in the process of positioning the system on the market. There are already some reactions. We have posted it on the well-known social media channels, because during corona times it is not possible to advertise at trade fairs or events. Our next step is to communicate with our direct customers. On the one hand, we are interested in the wind turbine manufacturers, because they could potentially include us in their service contracts and portfolio. On the other hand, we are of course also in contact with wind farm operators, because they are the ones who will have to pay for the downtime later on.

How did the idea for this innovation come about?

The Fraunhofer IOSB has been researching for some time to further develop laser Doppler vibrometry in order to accurately measure the vibrations of a wind turbine during operation. We found this very exciting and joined the WEADYN project as an industrial partner. Halfway through, we started thinking: The experimental setup for laser Doppler vibrometry is very interesting, but would it not also be possible to install a camera where the laser is located? And so the idea to develop this photo documentation system was born.

What happened next?

We then commissioned the Fraunhofer IOSB to develop and build such a plant for photo documentation. This was then no longer part of the research project, but a private sector contract with our own money. The prerequisites for the technology were established by the research project and combined with the new idea. And we were then able to apply for and obtain a joint patent for the photo documentation system. This patent was granted for Germany last year. At the moment we are in the process of applying for the international patent, which we have extended to other countries.

And the research project itself?

In this project, we were able to apply laser Doppler vibrometry, which is already used today to investigate and evaluate the vibration properties of stationary machines, to rotor blades during operation for the first time. As the project has been so successful, we have decided to also take over the industrial part in the follow-up project WEALyR. Here we are working together to further optimise the measurement system. This means: The vibration measurement should be fast, reproducible and also possible on a large number of plants.

What role does project funding play for you?

As an SME, we receive half of the funding for these research projects from the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. That means half of it comes from our own funds. Over the past three years, we have invested part of our profits to further develop the vibration measurement system. This industrial part has tripled to 770,000 euros in the new project. We could not have done this without the funding. And if we had not done it, no one probably would have. And then nothing would have come of it.

In other words, the research funding is what made it possible for us to do research on something like this with the Fraunhofer Institute in the first place. Otherwise, it would definitely have exceeded our own funds. Because the risk would also have been far too great. After all, research is always a risky endeavour. Research projects are distinguished by the fact that you never know one hundred per cent where the journey is going or exactly how to get to your destination. And for us as a modest SME, this is of course a highly risky investment. But now we have done it - also because of the funding - and are very happy with it. The results speak for themselves.

What experiences have you gained as an SME in the research projects?

I can only recommend it. Of course there are always a few difficulties and friction losses, but that is obvious. The combination of industry and research has two advantages: On the one hand, industry is learning what it means to do research. And that not everything is purpose-oriented, but that there are also tracks that may lead to a dead end, but from which you can get out again. And this is how innovations come about. Problem solving is a priority for the research institutions.

On the other hand, we are good for the scientists because in the end we can formulate the product. We know the requirements of the market and can intervene in a target-oriented manner if we notice that the research work is leading to a result that cannot be placed on the market.

What experiences have you had with the support provided by Project Management Jülich?

The staff supported us in the finer points of preparing the applications, both factually and professionally. That helped me a lot. And I also think that this is a very cooperative partnership, which I greatly appreciate and where we learn something new every day.

Jülich also offers new perspectives and cross-references to other research work. This creates nice synergies.

Holger Nawrocki is managing director and owner of Nawrocki Alpin GmbH. He studied history and German literature at the University of Greifswald and Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1995 he founded Nawrocki Alpin GmbH in Berlin for rope-assisted work at heights.